Your Guide to the Lunar New Year

新年快樂! Happy New Year!

The Lunar New Year is one of the most widely celebrated and fun holidays in the world, but most people in the West don’t know much about it. And so we’re going to journey across the ocean and back in time to explore the legends, customs, and tasty traditions of this ancient holiday, specifically, the Chinese New Year.

Chinese New Year Basics

Because the Chinese New Year is observed according to a lunar calendar, every year the festivities begin on a different date on the Gregorian calendar—ranging from late-January to mid-February. This Chinese New Year is on February 12, marking the first day of the Year of the Ox.

It’s a loooong holiday—there are altogether 23 days of festivities. Today, though, it’s rare to find people who celebrate and observe all the customs for each of these 23 days, and most partying is relegated to the beginning and end of the holiday.

Still, there’s a purpose behind each day. Let’s take a look:

Feb. 4 - Little Year (小年, xiǎo nián): Preparations begin.

Feb. 5-10 - preparations continue...

Feb. 11 - New Year’s Eve (除夕, chú xī): Big family dinner, gifts, and red envelopes of cash for the children.

Feb. 12 – New Year’s Day (初一, chū yī): Firecrackers, sharing blessings and greetings, and celebrating with family.

Feb. 13 - To the wife’s parents (迎婿日, yíng xù rì): Married daughters bring their husbands and children to visit her parents’ home.

Feb. 14 - Day of the Rat (鼠日, shǔ rì): According to folk tales, mice get married on this day.

Feb. 15 - Day of the Sheep (羊日, yáng rì): In Chinese mythology, the goddess Nü Wa created humans. According to legend, she created sheep on the 4th day of the new year.

Feb. 16 - Break Five (破五, pò wǔ): Markets and stores open again, and some taboos are lifted.

Feb. 17 - Day of the Horse (馬日, mǎ rì): Goddess Nü Wa created the horse on the 6th day.

Feb. 18 - Day of the Human (人日, rén rì): Nü Wa created humans on the 7th day.

Feb. 19 - Day of the Grains (故日節, gǔ rì jié): According to legend, agricultural grains came into existence on this day.

Feb. 20 - The Jade Emperor’s Birthday (天公生, tiān gōng shēng): The mythical Jade Emperor is celebrated on this day.

Feb. 21 - Stone Festival (石頭節, shí tou jié): 10th day of festival, and since rock (石) is pronounced the same as ten (十), this is, of course, the birthday of stone.

Feb. 22 - Son-in-Law’s Day (子婿日, zǐ xù rì): Fathers invite their son-in-laws over on this day.

Feb. 23-25 - Preparations for the Lantern Festival...

Feb. 26 - Lantern Festival (元宵節, yuán xiāo jié): This is a big one. People celebrate with all kinds of lanterns—round and red, different colored, and even lanterns in the shape of mythical creatures like dragons.

These lanterns also have a story behind them. Some two thousand years ago, Zhuge Liang, one of China’s most celebrated military minds, used a floating lantern to send calls for reinforcements when his troops were surrounded.

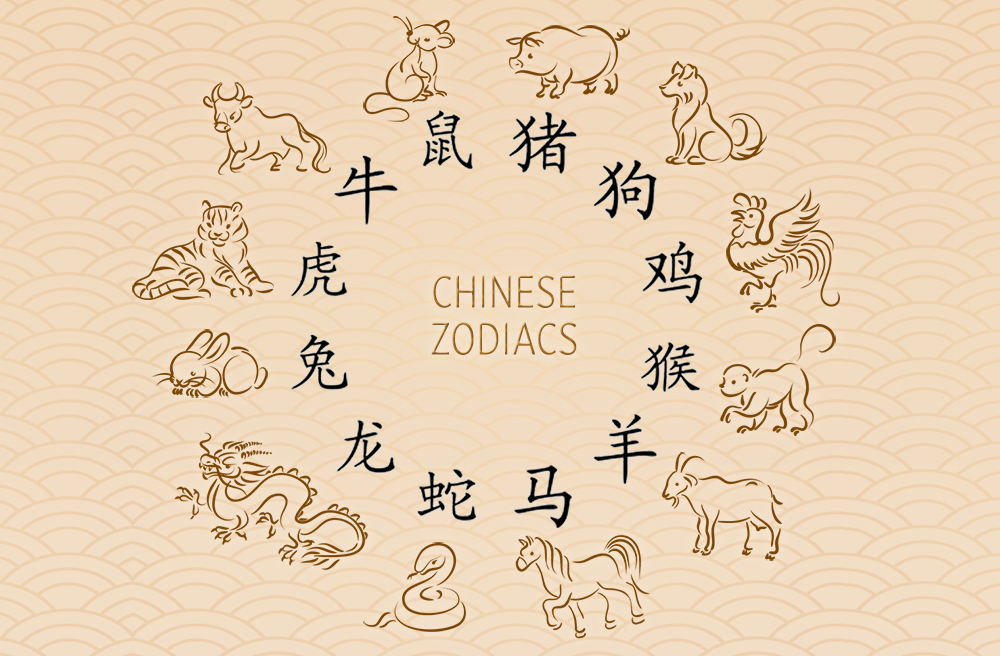

The Zodiac

The Chinese zodiac is a repeating 12-year cycle of animal signs corresponding to Chinese cosmology. In order, the zodiac animals are: Rat/Mouse, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat/Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig. Each animal has particular attributes, and those attributes are passed on to people born under each animal sign.

The Lunar New Year marks the transition from one zodiac sign to the next. Since last year was the Year of the Mouse, this upcoming one is the Year of the Ox.

In addition to the 12-year cycle of animals, there is a 10-year cycle of heavenly stems as well as a 5-year cycle of elements. Together, these cycles make a repeating 60-year cycle, and Chinese astrologers use this information to read a person’s personality, fortune, and compatibility with others.

Food

What would the most important holiday of the year be without lots and lots of delicious food? Since family is at the heart of Chinese culture, it’s no surprise that the New Year’s Eve dinner, or “reunion dinner,” is the most important part of the holiday.

While dishes differ from table to table, there are some common staples that symbolize prosperity during the coming year. For example, dumplings resemble gold ingots, long noodles bring longevity, and whole fish represents wealth and good fortune—that’s because “fish” (yú) has the same pronunciation as the word for “surplus.”

Other typical foods you might encounter are spring rolls, rice cakes (not the puffy cracker kind, but sweet glutinous rice flour cake), vegetable dishes, whole chickens, and—a common favorite—hot pot.

Customs & Traditions

There are many customs and traditions observed during Chinese New Year celebrations. Most of them originate either in legend or clever wordplay.

The earliest legend related to the Chinese New Year tells of the beast Nian (meaning “year”), that would come to terrorize villagers during the Shang Dynasty. After a while, people realized that Nian would only come once every 365 days, and also that Nian could be scared off by loud noises.

So next time Nian came to wreak havoc, the people were prepared and set off lots of fireworks, saving the village and starting a tradition that continues to this day.

There are also many New Year taboos. For example, it’s bad luck to say any negative things like “death,” “sad,” “sick,” etc., during the first several days of the New Year. Also don’t give someone a clock as a gift—since the word for “clock” sounds like the word for paying last respects, don’t use sharp items, and don’t break plates (only break china in Greece).

Traditional decorations for Chinese New Year include poetic couplets on each side of a doorway, intricate paper cuttings, colorful lanterns, auspicious words, and paintings depicting phoenixes, dragons, beautiful landscapes, and divine beings.

* * *

In a way, Chinese New Year is a microcosm of China itself. It’s complex, incredibly diverse, and rich in traditions that have been shaped and refined over thousands of years.

And at its heart, the New Year is about being thankful for life’s many blessings, and sharing those blessings with the one’s you love.

John Perry

Master of Ceremonies