Huizong: The Reluctant Emperor (Part 2)

As promised, here is part II of Huizong's story (Part I).

Sending the Wrong

Message

After peace resumed between the Song Dynasty and the kingdom of Jin, Grand Emperor Huizong and his elder son Emperor Qinzong spent their days throwing lavish parties in the imperial palace. But not for long.

In May 1126, the Jin sent two ambassadors to the imperial palace. When Emperor Qinzong discovered that the ambassadors were nobles from the former Liao, he secretly invited them to join forces in an anti-Jin alliance. But, instead, the ambassadors relayed the message to the Jin, who were enraged and declared war again.

The Fast and the Furious

The Jin soldiers, who had just returned home from the previous battle against the Song, were quickly mobilized. Learning from their mistakes, they beefed up their forces and went straight for the capital, relying on speed and sheer numbers.

By contrast, the Song had already sent its soldiers and generals away from the capital. Lacking experienced generals, the Song’s defenses were a mess. They called for aid and got responses from all over the country, including from Huizong’s younger son, who personally led troops to his father and elder brother’s rescue.

But the Jin forces were faster and besieged the capital. On January 9, 1127, the Song capital, Hangzhou, fell. The Jin captured Grand Emperor Huizong, his son Qinzong, as well as the entire royal court—ministers, attendants, and servants totaling 14,000 people—and sent them on a forced march to Manchuria. Many died before they got there.

A General’s Lament

Rarely had China faced the humiliation of having emperors kidnapped and deported. This incident went down in history as Jing Kang zhi chi: the “Humiliation of the year of Jing Kang” (Chinese emperors used to give each year of their reign its own name. Ironically, Jing Kang means “quiet, peaceful well-being.”).

This phrase was immortalized in General Yue Fei’s famous poem, “The River Runs Red”:

Jing Kang Chi, you wei xue,

chen zi hen, he shi mie?

The Humiliation of Jing Kang lingers, revenge has yet to be served,

The loyal subjects lament, when shall it be extinguished?

With the Grand Emperor and his son in exile, the Song was under the rule of Emperor Gaozong, Huizong’s younger son, and engaged in constant border skirmishes with the Jin. In these battles, General Yue Fei was the foremost leader.

Sadly, things did not go well for either the general or the captured emperors. After Yue Fei fought the Jin for a decade, a corrupt, vengeful court official named Qin Hui convinced Emperor Gaozong that it would be better to forget about rescuing his father and older brother from the Jin. If they came back, wouldn’t Gaozong have to yield the throne?

End of an Era

In truth, Qin Hui hated Yue Fei, who was a remarkable general, poet, and upright person. People loved their general and treated him as a hero. Qin Hui, mad with jealousy, tricked the emperor into ordering Yue Fei back to the capital to stand trial for treason.

It was such a ridiculous ruse that Yue Fei and his men recognized it immediately. His soldiers begged him to stay, even offering to support him as the next emperor, but the loyal Yue Fei chose to obey the imperial summons.

At the capital, Qin Hui tried Yue Fei in a closed court but couldn’t produce any evidence of treason. So he simply ordered an immediate execution.

With the peerless Yue Fei gone, the Jin kept their hold on the lands beyond the Song’s northern borders. Thus, the truncated Song became known as the Southern Song Dynasty.

Meanwhile, in the Jin capital, the exiled Song emperors lived like prisoners. Huizong never got another chance to put brush to paper and succumbed to cold and starvation, dying in exile with his son.

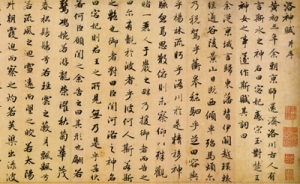

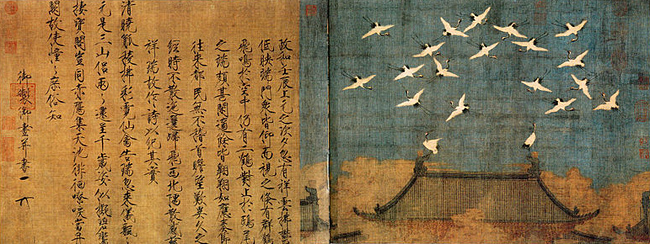

A Portrait in Script

So why do we admire Emperor Huizong today? As an emperor, he failed miserably by neglecting state affairs, indulging in frivolous pastimes, and running from the enemy. But he left a legacy as a scholar and artist with a striking calligraphy style.

Aesthetically speaking, Huizong’s “Slender Gold Style” doesn’t appeal to me—it’s too fine and fragile, thin to the point of breaking, as if the slightest puff would scatter it to the four winds. It has neither the grand, majestic air of Tang Dynasty script, nor the elegant poise of Qing Dynasty characters.

Yet still it fascinates. Better than any painting, clearer than any portrait, it is the definitive profile of a scholar who couldn’t, wouldn’t, and shouldn’t have ever been an emperor.

Jade Zhan

Contributing writer

January 15, 2013