Classical Chinese 101 (Part 3)

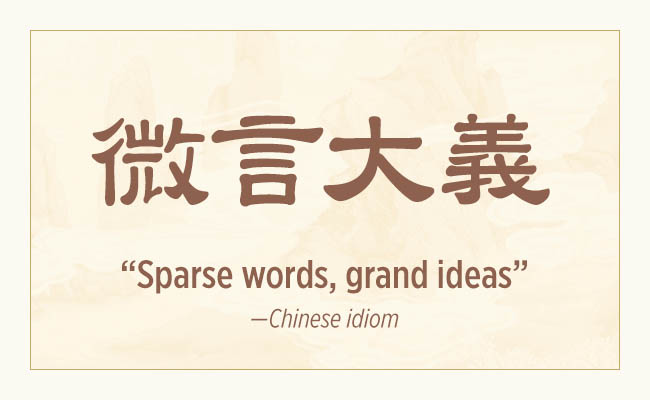

In this article, I want to introduce you to the hidden beauty of classical Chinese.

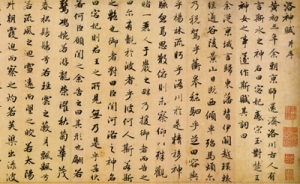

Recently I read the piece “Memorial on the Yueyang Tower,” written by the statesman and philosopher Fan Zhongyan (989 - 1052 C.E.) during the Song Dynasty.

The first time I heard this piece read aloud, I thought it was theatrical, exaggerated, and ostentatious. But after studying the text, understanding the meaning, and developing an appreciation for the elegant vocabulary and phrasing, I now think that this is an accurate reflection of just how powerful this piece of literature is.

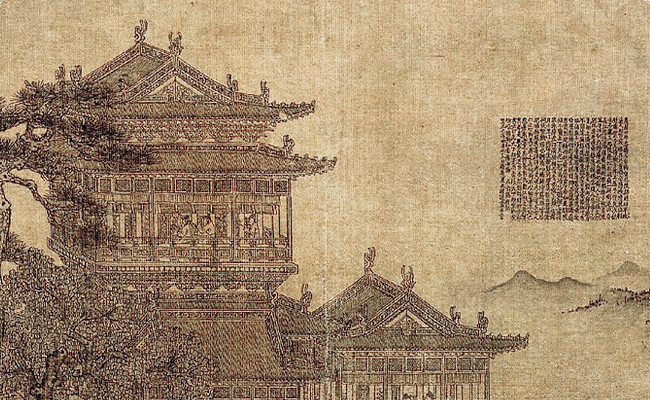

“Memorial on the Yueyang Tower” was written by Fan Zhongyan for a friend, a governor who was rebuilding the tower in question. Incidentally, although this article describes in vivid imagery the tower and its surroundings, Fan was nowhere near the tower when he wrote it. In fact, he was only sent a painting of it along with his friend’s request. He wrote it entirely using his imagination.

And I think this is the most powerful element of classical Chinese—how the author's imagination and the ideas of the reader blend together. Classical Chinese implies things subtly, trusting in the ability of the reader to interpret the words flexibly, without an abundance of explanation.

Nowadays, many Chinese people see classical Chinese as archaic, overly complex, and opaque. They complain that in order to even understand classical Chinese, you need a broad lexicon and a wide-ranging knowledge of ancient texts and historical references.

But I think this is a good thing. For me, a language that assumes you have a certain level of knowledge benefits society. The modern trend of instant messaging, tweeting, texting, and hashtags, serves only to turn everyday writing into a lazy shorthand of g2g, lol, sup, #meaningless. For quickly communicating ideas, that’s totally fine. But I think there is nothing wrong with having a more complex way of expressing ourselves, showing finesse, and realizing our thoughts.

I admit that modern Chinese is more approachable, easier to parse, and far simpler to write. But the simple way is not necessarily the best way.

Think about that favorite novel of yours, the one you adored as a child, the one where all the characters seemed to come alive off the page, the one where every scene was firmly imprinted into your imagination…

…And then it became a movie, starring actors who looked completely different from what you had imagined, in scenes completely different from those you dreamt up, in a world unrecognizable from what you had painted. The movie is easy; no reading required, no thinking required, just sit back, relax, enjoy.

But with a movie, there is no room to see differently. To imagine differently. To dream differently.

The power of classical Chinese lies not just in what is written, but also in what is not written, what is not explicitly explained. The power of classical Chinese lies in what is left for you to think about.

Jeff Shao

Contributing writer